AgEBB-MU CAFNR Extension

Green Horizons

Volume 25, Number 3

Fall 2021

|

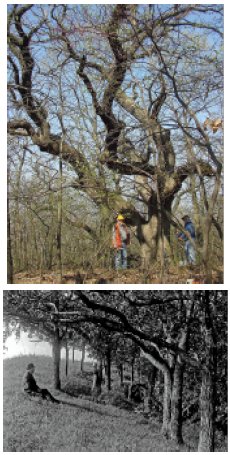

| In 1949, the great American conservationist Aldo Leopold wrote "...he who owns a veteran bur oak owns more than a tree. He owns a historical library, and a reserved seat in the theater of evolution." With both respect to Leopold and deference to women, the author adds that female owners of bur oaks are equally fortunate. With its armor-like bark and majestic branches, the bur oak-like this famous one in McBaine, Missouri-is one of America's most stately tree species. |

The Mighty Bur Oak: Sentinel Tree of the Prairie Peninsula

Mike Leahy, Natural Community Ecologist, MDC

The acorn is what I noticed first. On a hike with my family last winter to a favorite bottomland forest in central Missouri, at my feet was an enormous acorn with a fringed cap-the unmistakable touchstone of the majestic bur oak. When I approached the solid tree, with its enormous limbs and a trunk armored with deeply furrowed bark, I was in the presence of a solemn living marker of tree time.

In our distracted human world of tweets and live streams, in front of me was a being marking the ages. In my own time on earth, bur oaks have been a steadfast component of my knowledge of the natural world. Beginning with early childhood visits to the Morton Arboretum outside of Chicago, and continuing to the present-both as a natural community ecologist and as an adherent of nature-I have always been humbled by this sentinel tree of both bottomland forests and prairies.

Bur Oak Geography

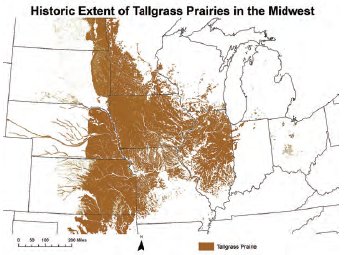

Bur oak is the signature tree species of the tallgrass prairie peninsula. This historic vegetative region stretches from the Flint Hills of Kansas east to Ohio and north into Wisconsin. Of the 90 species of oak in the United States, bur oak is the most widely distributed and ranges farthest north (Nixon, Flora of North America Editorial Committee 1993+; McWilliams et al. 2002). Occurring from Saskatchewan south to Texas and east to New Brunswick, bur oak persists across an annual precipitation gradient from as low as 15 inches to more than 50 inches (Johnson 1990). It is the most cold tolerant of oak species (McPhee and Loo 2009) and one of the most droughttolerant oaks as well (Abrams 1990).

In Missouri, bur oak occurs across the state but is never very common. It is more frequently found in the adjacent states of Illinois, Iowa, Nebraska, and Kansas. In Missouri, bur oak occurs in both upland and bottomland habitats in the northern half of the state, whereas it usually occurs only in bottomland habitats in the southern half.

Life History

Bur oaks are monoecious, having male flowers (catkins) and female flowers (inconspicuous, in leaf axils) on the same tree. Bur oaks also are dichogamous, meaning that male oak flowers of individual trees release pollen before female flowers are receptive, to prevent self-pollination (Great Plains Flora Association 1986). In Illinois, researchers have found that bur oak populations-despite being dispersed and fragmented-appear to comprise a single genetic population (Craft and Ashley 2007) likely due to high levels of gene flow from long distance pollen dispersal.

|

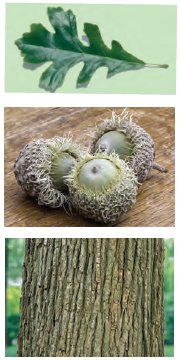

Bur oak (Quercus macrocarpa) belongs to the Fagaceae plant family and the oak genus Quercus. It is in the subgenus Leucobalanus, lacking bristles on the leaf lobes or apex. Its alternate leaves include 3 to 8 lobes per side with at least one pair of deep sinuses at or below the midpoint. Leaf blades are 5 to 9 inches long and 3.5 to 5 inches wide. Major veins on the leaf undersurface lack conspicuous tufts of hairs. Twigs are usually pubescent. It has the largest acorns of all North American oaks, with the nut being 1 to 2 inches long (Yatskievych 2013). With durable, high quality wood, bur oak lumber is used for cabinetry, barrels, hardwood flooring and fence posts. Its ecological value is extremely important, as a host plant for caterpillars of many butterfly and moth species, and as a producer of acorns that feed wildlife. |

The typical age trees being acorn production is 35 years with optimal acorn production from trees that are between 75 and 150 years old (Young and Young 2009), but trees in ideal conditions have been known to produce in as little as 7 to 9 years. Bur oaks produce the largest acorns of any oak species north of the Rio Grande River. Bur oak acorns are mature around four months after pollination, and they drop in autumn. Bur oak does not always germinate in the autumn. Rather, it requires a period of 30-60 days for root emergence, then additional chilling for the shoot (or epicotyl) to emerge. In general, germination appears to decrease with desiccation and likely acorn age (Johnson 1990). Little research has occurred on the best substrate for germination; one study in Iowa found germination was best for acorns buried one inch in mineral soil with no leaf litter (Krajicek 1960).

Good seed crops occur every two to three years. Acorns are dispersed by gravity, rodents, and to a lesser extent, water. Acorn predation by weevils (Curculionidae) can be significant (Kearby et al. 1986). Bur oak acorns are a food source for a variety of birds and mammals, and high levels of predation are common in bur oak habitats (Briggs and Smith 1989). In the Flint Hills of Kansas, bur oaks form savanna/woodland communities in riparian areas, termed locally as "gallery forests" surrounded by upland tallgrass prairie. Fox squirrels here have been documented caching bur oak acorns upslope as much as 169 feet into the prairie (Stapanian and Smith 1986).

Bur oak seedlings rapidly develop deep taproots (Danner and Knapp 2001) and produce extensive root systems with wide-spreading laterals. For example, a 12-year old, 14-foot tall bur oak in southeastern Nebraska on silt loam soil had a 13-foot deep taproot and lateral roots extending 11.5 feet (Sprackling and Read 1979).

|

| This map of the tallgrass prairie peninsula-where the bur oak is most abundant-was obtained from pre-Euro-American settlement vegetation layers for each state, except North and South Dakota, which are from the LANDFIRE Biophysical Settings layer. |

Despite their rapid root growth, overall, bur oaks are slow growing. On mesic soils of floodplain terraces and footslopes, mature trees generally grow 80 to 100 feet tall, with a diameter of 36 to 48 inches (at 4.5 feet above the ground) and can live 200 to 300 years (Johnson 1990). The oldest living documented Missouri bur oak was 408 years old (Stambaugh 2020). Mature trees grown under good conditions have a large trunk, broad crown, and large branches.

As Aldo Leopold wrote in 1949, "Bur oak is the only tree that can stand up to a prairie fire and live." Younger bur oaks, if top killed by fire or cutting, readily resprout. As bur oaks mature they develop one of the thickest barks of North American deciduous trees, which serves as a protective insulation from fire (Peterson and Reich 2001). Bur oak "grubs" are burl-like woody structures that develop on the soil surface as young bur oak stems or sprouts are repeatedly top-killed by fire. These "grubs" have been noted as a common feature of bur oak savannas in southern Wisconsin and northern Illinois (Curtis 1959). With cessation of fire, these bur oak savannas with their "grubs" quickly formed dense thickets of bur oak and lost their prairie vegetation (Bowles and McBride 1998).

In his book, The Story of my Boyhood and Youth, John Muir recalls every detail of growing up in Marquette County, Wisconsin: "As soon as the oak openings were settled, and the farmers had prevented running grass-fires, the grubs grew up into trees and formed tall thickets...and every trace of the sunny 'openings' vanished." In the loess hills of northwestern Missouri, remnant prairies cling to the steep west- and south-facing slopes. These loess hill prairies harbor unique assemblages of plants and animals more similar to Great Plains mid- and short-grass prairies than to other Missouri ones.

|

At top, Rich Guyette and George Hartman with the University of Missouri's tree ring lab in front of an old-growth bur oak at the Missouri Department of Conservation's Brickyard Hill Loess Mound Natural Area in northwestern Missouri. At bottom, the east slope of Brickyard Hill Loess Mound Natural Area, circa 1912, with bur oaks. |

On the protected north- and east-facing slopes of some sites, such as at Brickyard Hill Conservation Area's Loess Mound Natural Area, are groves of old-growth bur oaks that historically supported oak savannas. Here researchers Mike Stambaugh and Rich Guyette with the University of Missouri's tree ring lab sampled live and dead trees to extract cross sections of their wood (Stambaugh et al. 2006). They were able to recon-struct a 334-year tree-ring record spanning the period 1671 to 2004. Pre-1820, the mean fire interval was 6.6 years-that is on average a fire hot enough to scar a sample tree once every 6.6 years. For a period after Euro-American settle-ment of the area, the mean fire interval dropped to 2.5. Then, with the advent of fire suppression, only one fire scar was found after the mid-1950s. Although the loess hill prairies here have been treated with prescribed fire and thinning, efforts to restore the bur oak savannas on the protected slopes are just beginning.

Habitats

Bur oaks typically occur on more calcareous soils and are associated with the Alfisol and Mollisol soil orders. In Missouri bur oak is rarely a dominant overstory tree as it is in states to the north, east, and west (notably Minnesota, Wisconsin, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, Nebraska, and Kansas). Here, according to U.S. Forest Service Forest Inventory and Analysis data, bur oak occurs most commonly in the Central Dissected Till Plains or Glaciated Plains ecoregion of northern Missouri and in the Osage Plains ecoregion. In these ecoregions, bur oak occurs in uplands as well as on terraces and higher elevations in bottomlands.

Scattered bur oak stands in Missouri occur along larger Ozark rivers such as the Current on higher terraces and foot slopes. Many of the mature bur oaks along the Current River date back to the 1860s (Stambaugh 2020). Remnant bur oaks also occur in higher elevation bottomland forests of the Missouri and Mississippi river floodplains. Examples range from the now lone old growth bur oak near McBaine to scattered stands ranging from Westport Island Natural Area near Elsberry to Big Oak Tree State Park in the Bootheel.

Cultural History

Although not a major component of Missouri's timber supply, bur oak is often grouped with white oak (Quercus alba) in lumber manufacture. Bur oak is used for railroad ties, cabinets, flooring, and fuel (Kurz 2003). Bur oak groves in the prairie landscape of the Midwest were often highly valued by European American settlers as they provided wood for homes and fuel, and acorn forage for livestock (Nuzzo 1986). Native Americans utilized bur oak as a food source (acorn meal) and for some medicinal properties (e.g., the inner bark was used as an astringent). Undoubtedly, they would have used bur oak groves for shade and wind protection for encampments, and for fuel wood and tools.

There are historic photos from the 19th century taken by European Americans of bur oak "burial trees" used for aboveground burial by some Native Americans from the Great Plains (Stein et al. 2003). Certain large bur oaks were also used as "council trees." The Council Oak at Sioux City, Iowa, was a bur oak. Here during the week of August 13 to 20 in 1804, the tree shaded a meeting between the Lewis and Clark expedition and Native Americans.

Conservation with Land Use Changes

In many parts of the Midwest, bur oak has decreased in abundance and extent over the last century. Many prairie bur oak groves were converted to settlements, non-native pasture grasslands, or row crops. In the bottomlands, bur oak occupied some of the choicest lands for row crop agriculture, and these areas were rapidly converted. Fire suppression led to prairies and savannas becoming bur oak thickets, which then became too shaded for bur oak regeneration and recruitment and changed to mixed stands of elm, ash, hickory, and maple.

Pest Problems of Concern

In Iowa, a bur oak blight has been noted that led to significant leaf and then branch mortality of upland bur oaks. Researchers at Iowa State University (Harrington and McNew 2016) determined that the cause of this disease is a fungus, Tubakia iowensis.

The host specificity and genetic variation in the pathogen and apparent variation in susceptibility in the host (bur oak) suggest that this fungus is native. Consecutive springs of high rainfall in Iowa during bud break and shoot expansion are believed to increase severity of the disease in individual trees, and led to the recent recognition of the disease. In Iowa a marked increase in spring rainfall during the last two decades coincided with this disease's recognition by science.

Tree mortality typically doesn't occur due to infection by T. iowensis alone. Usually it is a combination of the fungal infection and then an infestation of a native beetle-the two-lined chestnut borer (Agrilus bilineatus). The larvae of the borer construct feeding galleries in oak tree xylem that can lead to dead crown branches and tree death over a two- to four-year period (Haack and Pretrice 2020). Also, trees stressed by previous droughts, late spring frosts, and hail and ice storms are susceptible to borer infestations.

Literature Cited

Abrams, M.D. 1990. Adaptations and responses to drought in Quercus species of North America. Tree Physiology 7: 227-238.

Bowles, M.L. and J.L. McBride. 1998. Vegetation composition, structure, and chronological change in a decadent midwestern North American savanna remnant. Natural Areas Journal. 18 (1): 14-27.

Briggs, J.M. and K.G. Smith. 1989. Influence of habitat on acorn selection by Peromyscus leucopus. Journal of Mammalogy. 70(1): 35-43.

Curtis, J.T. 1959. The vegetation of Wisconsin. Madison, WI: The University of Wisconsin Press. 657 p.

Danner, B.T. and A.K. Knapp. 2001. Growth dynamics of oak seedlings (Quercus macrocarpa Michx. and Quercus muhlenbergii Engelm.) from gallery forests: implications for forest expansion into grasslands. Trees. 15(5): 271-277.

Great Plains Flora Association. 1986. Flora of the Great Plains. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas. 1392 p.

Haack, R.A. and T.R. Petrice. 2020 Agrilus bilineatus. European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization (EPPO) Bulletin 50, no. 1 (2020): 158-165.

Harrington, T.C. and D.L. McNew. 2016. Distribution and intensification of bur oak blight in Iowa and the Midwest (Project NC-EM-B-10-01). In: K.M. Potter and B.L. Conkling (eds).

Forest health monitoring: national status, trends, and analysis 2015. Gen. Tech. Rep. SRS-213. Asheville, NC: US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Southern Research Station. 226 p.

Johnson, P.S. 1990. Quercus macrocarpa Michx. Bur oak. In: R.M. Burns and B.H. Honkala, technical coordinators. Silvics of North America. Volume 2. Hardwoods. Agric. Handb. 654. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service: 686-692.

Kearby, W., D. Christisen and S. Myers. 1986. Insects: their biology and impact on acorn crops in Missouri's upland forests. Missouri Department of Conservation Terrestrial Series 16: 1-46.

Krajicek, J. 1960. Some factors affecting oak and black walnut reproduction. Iowa State Journal of Science 34(4): 631-634.

Kurz, D. Trees of Missouri. Missouri Dept. of Conservation.

Leopold, A. 1949. A Sand County almanac, and sketches here and there. Oxford University Press, New York.

McPhee, D.A. and J.A. Loo. 2009. Past and present distribution of New Brunswick bur oak popula-tions: a case for conservation. Northeastern Naturalist. 16(1): 85-100.

McWilliams, W.H., R.A. O'Brien, G.C. Reese, and K.L. Waddell. 2002. Distribution and abundance of oaks in North America. In: W.J. McShea and W.M. Healy (eds.). Oak forest ecosystems: ecology and management for wildlife. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press: 13-33.

Nixon, Kevin C. Quercus. In: Flora of North America Editorial Committee, eds. 1993+. Flora of North America North of Mexico [Online]. 21+ vols. New York and Oxford. Vol. 3. http://floranorthamerica.org/Quercus. Accessed 12/30/2020.

Nuzzo, V.A. 1986. Extent and status of Midwest oak savanna: presettlement and 1985. Natural Areas Journal. 6(2): 6-36.

Peterson, D.W. and P.B. Reich. 2001. Prescribed fire in oak savanna: fire frequency effects on stand structure and dynamics. Ecological Applications. 11(3): 914-927

Sprackling, J.A. and R.A. Read. 1979. Tree root systems in eastern Nebraska. Nebraska Conservation Bulletin Number 37. Lincoln, NE: The University of Nebraska, Institute of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Conservation and Survey Division. 71 p.

Stambaugh, M. 2020. Personal communication with director of the Missouri Tree Ring Lab.

Stambaugh, M, R. Guyette, E. McMurry and D. Dey. 2006. Fire history at the eastern great plains margin, Missouri River loess hills. Great Plains Research 16: 149-159.

Stapanian, M.A. and C.C. Smith. 1986. How fox squirrels influence the invasion of prairies by nut-bearing trees. Journal of Mammalogy. 67(2): 326-332. [11978]

Stein, J., D. Binion and R. Acciavatti. 2003. Field guide to native oak species of eastern North America. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Morgantown, WV.

Yatskievych, G. 2013. Steyermark's Flora of Missouri, Volume 3, Revised edition. The Missouri Botanical Garden Press in cooperation with the Missouri Department of Conservation. St. Louis, Missouri.

Young, J.A. and C.G. Young. 2009. Seeds of woody plants in North America. Revised and enlarged edition. Timber Press, Oregon.