AgEBB-MU CAFNR Extension

Green Horizons

Volume 24, Number 1

Winter 2020

Specialty Crops

Species Spotlight: Ozark chinkapin

Castanea ozarkensis

By Dr. Ron Revord | Center for Agroforestry, University of Missouri

|

In 1904, a fungal disease was discovered on American chestnut trees (Castanea dentata) that abruptly began dying in New York City. The pathogen was new to the United States, and its disease quickly progressed to girdle the tree's trunk and render itself fatal. In the coming years, the disease rapidly spread outward from New York City through the endemic range of the American chestnut. By the 1930's, the American chestnut was imperiled. The species that held a prominent keystone role in Appalachian forests for thousands of years was diminished to a rarity and in danger of extinction. This disease was of course the chestnut blight (Cryphonectria parasitica), which was later learned to have been imported on resistant Chinese and Japanese chestnut nursery stock. While the blight epidemic of the American chestnut is well known, and many great strides have been made toward its conservation and breeding blight resistance, the epidemic of its western relative, the Ozark chinkapin (Castanea ozarkensis) has trailed in its shadow.

|

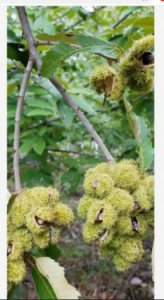

Top: Ozark chinkapin leaves and nuts, Bottom: Ozark chinkapin bark, Image from: https://ozarkchinquapinmembership.org/ |

The Ozark chinkapin is a species of chestnut native to the Ozark plateau in Arkansas and southern Missouri. Prior to the introduction of chestnut blight from Asia in the late nineteenth century, the Ozark chinkapin was a fixture in the regional ecology and culture. The trees reached up to 60 feet tall and produced many pounds of sweet, edible nuts enjoyed by wildlife, livestock, and humans alike. However, like the American chestnut, the species has been under severe pressure since the arrival of the blight, and today the Ozark chinkapin is in threat of extinction. Surviving plants have been reduced from canopy trees to diseased shrubs, which persist in a cycle of growth and dieback to shed blight-infected stems. These plants seldom have stems for a period long enough to reach a flowering stage, and consequently, new seedlings are not replenishing these populations as they slowly lose more plants to the blight.

While increasingly rare, diseased Ozark chinkapin can occasionally be found in conservation areas, along roadsides, and on farms. These remnant individuals and populations offer an incredible opportunity to conserve the species despite its recent population decline. Surprisingly, few systematic efforts for plant material conservation have been pursued for the Ozark chinkapin. The Missouri Department of Conservation (MDC) and the Center for Agroforestry have recently partnered to address this conservation gap, and with MDC's support, University of Missouri researchers are organizing a multi-phased plan to facilitate breeding blight resistance into a collection of genetically diverse Ozark chinkapin.

Selecting plant populations and individuals for collection assembly and conservation is complex and involves many factors. However, maximizing genetic diversity is frequently a priority. High levels of genetic diversity will improve the ability for the resulting restorations to adapt to future conditions, leaving them better protected against biological or climatic stressors.

Any effort to conserve or restore Ozark chinkapin has a higher likelihood of sustainable success if the distribution of genetic diversity across its geographic range is well characterized. This information can inform the structure of plant collection, breeding programs, and the eventual distribution of blight- resistant plant materials for restoration. Accordingly, University of Missouri researchers are first taking a thorough approach to finding Ozark chinkapin populations across its native range. With colleagues, we will study the genetic structure of these populations and reduce the studied plant populations down to a pool representative of the species' genetic variation. These plant selections will then be propagated and preserved in a field repository at the University of Missouri so they can be used in an organized breeding effort to develop blight resistant populations. We are currently organizing Ozark chinkapin collection trips for 2020. If you have information about plant populations in your area, please contact Dr. Ron Revord at r.revord@missouri.edu.

Chinkapin or chinquapin?

According to Webster's dictionary, both forms of this tree's name are correct. Chinquapin is the older of the two spellings derived from an Algonkian word which meant great seed. The Ozark Chinquapin Foundation lays out the unique history of the name on their Facebook page saying:

Captain John Smith was the first person to record the name Chinkuapin in his 1624 General Historie of Virginia. In it Smith states, "They {the Indians} have a small fruit growing on little trees, husked like a chestnut, but the fruit most like a very small Acorne. This they call Chechinkuamins, which they esteeme a great daintie." The chinkuapins Smith observed were likely the Allegheny chinkapin based on geography.

Within the last decade, scientists determined the Allegheny (Castanea pumila) and Ozark (Castanea ozarkensis) chinkapins are different species. Therefore, it would be fitting to differentiate the two by spelling. Officially, both versions of the name are acceptable!

|

Photo credit: Ron Revord |

|

Image from: Ozark Chinquapin Foundation |