AgEBB-MU CAFNR Extension

Green Horizons

Volume 23, Number 1

Winter 2019

Agroforestry

To Fertilize, or Not to Fertilize? That is the Question!

By Hank Stelzer| MU Extension, School of Natural Resources

I often get asked the question by woodland owners, "Should I fertilize my trees? And if so, what should I apply, when, and how much?" After a brief pause (for dramatic effect), I reply in my most professional Extension voice, "It depends." Seriously, these are very valid questions and it truly does depend; it depends whether you are managing a walnut (or other fine hardwood) plantation or a natural woodland, the predominating soil type, and the nutrient levels found in both the soil and the trees.

Walnut Plantations

The most common justification for spending one's time and money on fertilizer is for early tree growth and increased nut production once the trees begin bearing nuts. Vegetative growth (shoots and roots) and reproductive growth (flowers and nuts) require a lot of nutrients to keep trees healthy and productive.

Nitrogen (N) is usually the most in-demand nutrient in a tree. This is because it is involved in cell growth and development throughout the entire tree. Two other nutrients, phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) are normally applied at the same time nitrogen is applied. Hence, the reason most formulations contain all three elements. The numbers on a fertilizer bag represent the percent by weight of each element. Conventional fertilizer labeling lists in order the percentage of actual nitrogen, and the percentage of phosphorus and potassium expressed in the oxide form. For example, a 50-lb bag of 10-5-5 indicates that it has 5 lbs of actual nitrogen, and 2.5 lbs each of P2O5 and K2O.

For young walnut trees, only a minimum fertilization is required. Many producers apply 1/4 to 1/2 cup of a balanced, general purpose N-P- K 15-15-15 fertilizer to every young tree two times during the growing season; one application in March and the second one in June. This is to ensure sustained growth throughout the growing season. The trees must be watered after the fertilizer is applied. If one misses the June application, do not apply it later than the Fourth of July. A late application of nitrogen may favor continued growth into September and cause trees to be susceptible to damage from an early frost.

Once the plantation begins producing nuts, most producers apply nitrogen fertilizers with conventional equipment across the entire orchard floor, again in two applications; 60 lbs. actual nitrogen/acre during the first part of March and 40 lbs. actual nitrogen/acre in June.

While this is a common practice, it is necessary to do your own research before fertilizing. Every field is different and has different needs. Checking the soil nutrients and pH is vital before applying any fertilization method. Leaf analysis is very important in order to diagnose and correct nutrient deficiencies in walnut trees.

Soil samples should be taken during the winter months before any fertilizer is applied in the spring. Foliar samples should be taken after the leaves are fully expanded (usually late June) and before the tree begins to redistribute nutrients to other parts of the tree for nut production and in preparation for the coming winter. In both cases, one should take random samples across the plantation, combine them together, and then take a sample from the bulk collection. Contact your regional Extension agronomist for assistance. They will be happy to help!

|

|

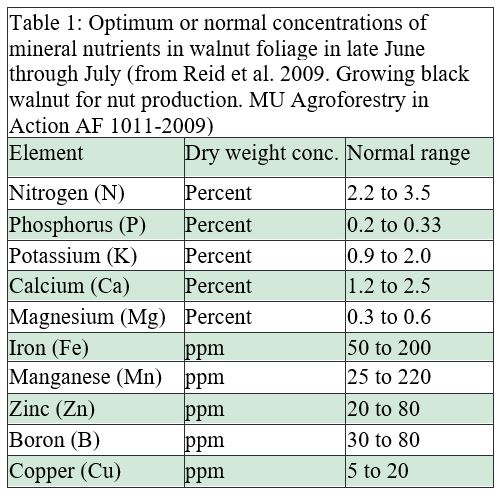

A word of caution when interpreting soil and foliage test results. While scientists may have determined "optimum nutrient concentrations" in black walnut foliage (Table 1), getting mineral nutrients applied to the soil into the leaves to achieve those "optimum" levels can be another story. This is because nutrient availability in the soil is determined by many factors, from soil structure to pH to level of organic matter to...well, you get the picture. And trees are like people: no two individual trees take up nutrients and utilize them the same way. Once again, your Extension agronomist can help you interpret test results and determine the best course of action.

What About Woodland Trees?

Some woodlands are naturally flush with nutrients. Plant-available minerals in the soil come from the weathering of rocks, deposition of soil relocated from somewhere else, and from the recycling of decomposed organic matter from dead plants and animals on the site. Their continual cycling between soils and trees is vital to the maintenance of soil minerals. But, some soils are just naturally depauperate and some have been exhausted by erosion or poor management practices. Minerals can also be leached from soil over time. Such losses of essential nutrients lead to deficiencies that reduce growth and jeopardize forest health.

So can you fertilize a woodland? Yes. Is it practical? Probably not. Also, keep in mind there are many possible reasons beyond fertility why your woodland might be exhibiting slow growth, discolored or misshapen foliage, or dieback. Fertilization simply will not fix the limitations of a site that is too wet or too dry, and it cannot overcome improper harvesting practices that erode soils or damage tree stems and roots.

Similarly, fertilization cannot prevent defoliation by insects (in fact, it might just nourish them). And an overcrowded stand where trees have no room for expansion will likely benefit far more from a good thinning. Fertilization won't improve the growth of trees already growing on a nutrient-rich site, and if overdone, it can actually have a deleterious effects on trees and the greater environment. Indeed, high soil concentrations of even the most essential nutrients can be toxic to plants and excessive nutrients can run off and pollute nearby waters. Fertilization may be a workable idea if you are trying to reforest an abandoned field and you are heaven-bent on restoring its vegetation. Otherwise, it's probably not worth the associated expense, practical difficulties, or environmental risks.