AgEBB-MU CAFNR Extension

Green Horizons

Volume 20, Number 2

May 2016

Forest Management

Returning Fire to Forest Management Part 2:

Balancing Challenges and Opportunities

By MICHAEL C. STAMBAUGH | Res. Asst. Prof., Forestry, University of Missouri

By DANIEL C. DEY | Research Forester, U.S. Forest Service

In Part 1 of the last issue of Green Horizons, we reviewed the history of fire in Midwestern forests and described "The Rub" when determining if burning is appropriate forest management. In this article, we further describe common challenges and opportunities that landowners face when deciding on the use of fire to manage their forests.

Challenges

There are many challenges with fire management of forests, but one of the greatest is fire damage to valuable timber-this is particularly true for hardwoods. Fire may injure trees when the living cambium located just under the bark is heated and killed. Tree susceptibility to fire injury varies widely. Trees with thin bark (maples, elms, dogwood) are injured more readily than trees with thicker bark (oaks, hickories, ash). Smaller trees are more readily injured than larger ones. Once injured, some tree species are better at healing and resisting decay. High value trees, like black walnut or veneer quality oak, have much greater potential for value loss than trees with lower value.

|

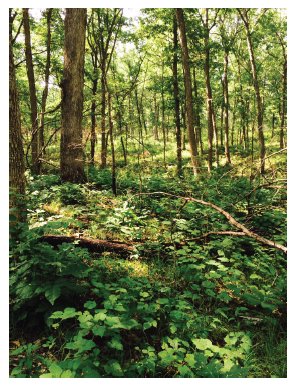

White oak-dominated forest that has undergone two low intensity prescribed burns in last five years. Note the open conditions allowing distant views, abundant herbaceous ground cover, partial sunlight, and lack of leaf litter. Photo credit: M. Stambaugh |

Fire-damaged trees are often deemed cull or worthless--this is not necessarily the case. For instance, fire injury that occurs within a very few years before harvesting, may have little or no effect on tree volume or value. Often, only the lowest portion of the tree is injured. For low intensity fires, injuries may be non-existent or confined to an area very low on the stump or butt log. Although the butt log typically contains most of a tree's merchantable volume and is usually the most valuable log in the tree, defect and decay resulting from fire injury may be largely contained outside of the scaling cylinder and is removed in slabwood during milling. Time since fire injury is also important because wood decaying organisms cause most of the damage and loss, and it takes time for decay to progress in trees. When planning to burn a forest, important factors to consider are: What are the management objectives and can they be met with burning? What is the expected fire behavior given the fuels, topography, and weather, and will this fire behavior meet the objectives? What is the value of trees and, if injured, how much economic value may be lost, both in the near-term and distant future? Other challenges include managing smoke, assessing fire risks, having the expertise to conduct a burn safely, covering the liability should the fire escape and damage a neighbor's property, and overcoming fears and historical paradigms (burning is bad).

Opportunities

Despite the challenges mentioned above, professional and private land managers are increasingly motivated to integrate fire into forest management due to the opportunities and benefits it provides. Often, the greatest opportunities relate to improving wildlife habitat by promoting mast producing species such as oaks and hickories, desired vegetation structure and composition, and native diversity of plants while increasing the amount and quality of forage and browse. Prescribed fire is used to manage for many wildlife species including whitetail deer, turkey, quail, and even some species of bats and migratory birds. Throughout the eastern U.S., burning is commonly recommended with the shelterwood harvesting technique as a means to promote oak regeneration for sustaining oak forests. Moreover, multiple burns increase the amount of light reaching the forest floor. Many of our wildlife species prosper in these open, park-like forest conditions (known commonly as woodlands and savannas) that were once dominant in Midwestern landscapes before fire suppression. Today they are some of the rarest natural communities, having been replaced by dense, closed-canopied forests that have a heavy leaf litter and low plant diversity.

Balance

Fire management of forests, woodlands and savannas is an old practice that is receiving renewed interest, especially on lands with multiple use objectives. Often, decisions to burn forests are not just based upon the standing trees but instead, on multiple factors. Ultimately, the land management objectives determines the value of the use of fire.