AgEBB-MU CAFNR Extension

Green Horizons

Spring 2022

Missouri Natural Resource Professionals Share Key Insights

for Including Agroforestry Practices in Conservation Programs

Raelin Kronenberg, Lincoln University Research Technician,

Center for Agroforestry Graduate Research Assistant alumna

While interest in agroforestry practices is growing throughout the state of Missouri, adoption remains slow (Valdivia et al. 2012; Trozzo et al, 2014; Lovell et al. 2018). To explore how natural resource conservation agencies connect with and support landowners who are interested in agroforestry, University of Missouri Center for Agroforestry researchers interviewed seven prominent natural resource professionals. These individuals were chosen based on their position to support private land conservation throughout the state of Missouri. Interview questions uncovered natural resource professionals' perspectives on landowner interest in planting trees, clarified how professionals build relationships with landowners, and assessed their knowledge and promotion of agroforestry practices to their clients.

Trees in Conservation: Great potential, Misunderstandings, & Room to Grow

The interviewed natural resource professionals shared insights into the current use of conservation program funding for tree planting. There are several conservation programs that support tree planting and agroforestry specifically. Missouri is unique in that it allocates part of its Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) funding specifically for agroforestry practices (Cartwright et al. 2017). While the professionals noted that opportunity exists to further agroforestry adoption through federal conservation programs, there are still several misunderstandings about the expectations and limitations of these programs. The conservation professionals emphasized a general confusion among both professionals and landowners about exact program standards and how agroforestry plantings would need to be maintained to ensure adherence to program requirements. Similar dialogs emerged in other survey works on agroforestry establishment and management (Lawrence and Hardesty 1992, Stutzman et al. 2019). Currently, there are no restrictions for using conservation program funds to plant trees and shrubs that produce edible products, and landowners are free to harvest products for personal use. Yet, several professionals mentioned they were unsure which tree species could be purchased and planted with program money, hinting at the tension between plantings for conservation and plantings for harvesting food or fiber products. One interviewee summed up,

"When we talk about the agroforestry under EQIP, we always have to remember that it's not primarily for the purposes of planting a food crop for the producer. Its primarily for the purpose of addressing a resource concern and it [agroforestry] just makes a really good fit."

The Challenge of Building Long-term Relationships for Long-Term Conservation

Since natural resource professionals are primary points of contact for landowners interested in implementing conservation practices, it is important to understand how they build relationships with landowners. All the professionals interviewed relied on landowners to reach out to them or their agency office, meaning there was little recruitment of landowners for enrollment in conservation programs. In addition, outreach efforts are turning increasingly digital with social media and email becoming key communication sources, as noted by one of the professionals interviewed.

"Social media has been really good... Every county extension office has a Facebook page and usually some other social media. And so that's been a good way to establish relationships and give the information of where they can find me at. And then they kind of, we kind of go from there as far as establishing [a relationship]."

However, most landowners still look to other sources for farming information, and this presents challenges with relying on digital platforms for communication. Research has found landowners rely on print media, such as magazines, peer-networks, and natural resource professionals as their preferred sources of land management information (Barbieri and Valdivia 2010, MacFarland et al. 2017). While these preferences may change as reliance on digital communications increases, it is important to engage in multiple modes of information sharing to ensure conservation and agroforestry messaging reaches a wide landowner audience.

Natural Resource Agencies Wish for Greater Agroforestry Knowledge and Promotion

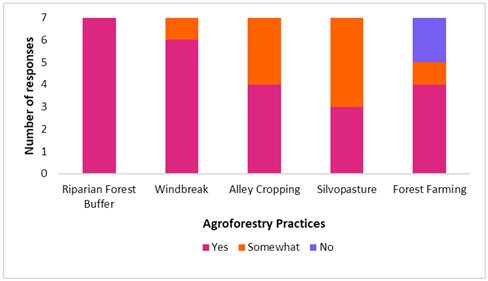

The final portion of the interviews focused on understanding natural resource professionals' knowledge and promotion of agroforestry practices to landowners. When asked about their familiarity with the five main agroforestry practices - windbreaks, alley cropping, silvopasture, riparian forest buffers, and forest farming - all professionals had some knowledge of these practices or had at least heard of the terminology. All professionals understood the concepts of windbreaks and riparian buffers, but they had differing levels of familiarity with the other three practices. Forest farming was the only agroforestry practice that two of the professionals had never heard of (Figure 1).

|

| Figure 1: Overview of natural resource professionals' familiarity with agroforestry practices. |

The natural resource professionals were also asked if they promote agroforestry to their clients. All the professionals said they tried to discuss agroforestry, but also stated they felt they could do more to actively promote agroforestry among landowners. There was general concern among the professionals with sending out the "right messages" about agroforestry to interested landowners.

"I think we do; we have done a good job of promoting agroforestry in Missouri. We can definitely do better. We just need to make sure we are sending out the right message."

The challenge natural resource professionals face in communicating the value of agroforestry is captured by the following quote.

"I'm probably guilty of not pushing it as much as I should sometimes, but I just, you got to have the right landowner to talk to. Because a lot of my landowners are typical stubborn old farmers that want to do things their way. I bring up planting trees in their grass they are going to just look at me like I'm crazy."

Many farmers are part of a legacy where their parents and grandparents worked to remove trees from their fields (Raedeke et al. 2003). Agricultural practices prevalent on the landscape today stem from a history of intensifying commodity crop production such as corn and soy. Ultimately, the acceptance of agroforestry will need to come from a cultural shift towards accepting trees within agricultural landscapes.

Overall, agroforestry practices with edible products are a promising component of conservation programs. The natural resource professionals interviewed were able to identify several beliefs and social factors that limit or support agroforestry in conservation programs. Despite the promise of agroforestry for conservation, there is a need for stronger information networks to ensure greater access to agroforestry knowledge for farmers, landowners, and natural resource professionals. It will also be crucial to dispel common misconceptions surrounding tree planting in conservation programs. Of particular importance is strengthening natural resource and conservation agencies' roles as educators and facilitators of agroforestry adoption. Additional research to further refine specific adoption factors and farmer profiles across regions of state will help determine which messages to send to whom. Finally, expanding educational opportunities for natural resource professionals on establishing, funding, and managing integrated tree-crop-livestock systems will be essential for expanding the use of agroforestry practices in conservation programs and agricultural production.

This work is supported by the University of Missouri Center for Agroforestry and the USDA/ARS Dale Bumpers Small Farm Research Center, Agreement number 58-6020-0-007 from the USDA Agricultural Research Service and by Award Number 2018-67019-27853 (subaward 090754-17910) from the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture.

Please direct questions or comments about this research to Raelin Kronenberg, email: KronenbergR@lincolnu.edu.

Citations

Barbieri C, Valdivia C. 2010. Recreation and agroforestry: Examining new dimensions of multifunctionality in family farms. J Rural Stud. 26(4):465-473. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2010.07.001.

Cartwright L, Goodrich N, Cai Z, Gold M. 2017. Using NRCS Technical and Financial Assistance for Agroforestry and Woody Crop Establishment through the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP). Agrofor Action.:1-4.

Lawrence J., Hardesty L. 1992. Mapping the territory?: agroforestry awareness among Washington State land manager. Agrofor Syst.(19):27-36.

Lovell ST, Dupraz C, Gold M, Jose S, Revord R, Stanek E, Wolz KJ. 2018. Temperate agroforestry research?: considering multifunctional woody polycultures and the design of long-term field trials. Agrofor Syst. 92(5):1397-1415. doi:10.1007/s10457-017-0087-4.

MacFarland K, Elevitch C, Friday J, ... KF-, Bentrup MM., 2017 U. 2017. Human dimensions of agroforestry systems. Agoforestry Enhancing Resilieny US Agric Landscapes Under Chang Cond.:73-90. https://www.fs.fed.us/research/publications/gtr/gtr_wo96/GTR-WO-96-Chapter5.pdf.

Raedeke AH, Green JJ, Hodge SS, Valdivia C. 2003. Farmers, the practice of farming and the future of agroforestry: An application of Bourdieu's concepts of field and habitus. Rural Sociol. 68(1):64-86. doi:10.1111/j.1549-0831.2003.tb00129.x.

Stutzman E, Barlow RJ, Morse W, Monks D, Teeter L. 2019. Targeting educational needs based on natural resource professionals' familiarity, learning, and perceptions of silvopasture in the southeastern U.S. Agrofor Syst. 93(1):345-353. doi:10.1007/s10457-018-0260-4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10457-018-0260-4.

Trozzo KE, Munsell JF, Chamberlain JL. 2014. Landowner interest in multifunctional agroforestry Riparian buffers. Agrofor Syst. 88(4):619-629. doi:10.1007/s10457-014-9678-5.

Valdivia C, Barbieri C, Gold MA. 2012. Between Forestry and Farming: Policy and Environmental Implications of the Barriers to Agroforestry Adoption. Can J Agric Econ. 60(2):155-175. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7976.2012.01248.x.